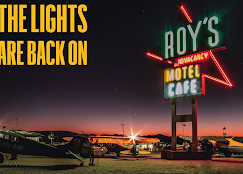

Celebrating 100 Years of Route 66 by Air

Explore resources designed to celebrate Route 66’s legacy and enrich your journey.

Historic Airports

Discover the stories of vintage airports along the Route 66 journey.

Aviation Pioneers

Learn about the aviators who shaped history along Route 66.

Route 66 Landmarks

Dive into the iconic stops that define America’s Mother Road.

100 Years of Route 66 Legacy

Discover upcoming centennial celebrations, fly-ins, and Route 66-inspired events that connect aviation enthusiasts and history buffs alike.

A Parallel History: The Aviation Legacy Along the Mother Road

To truly appreciate the concept of a Route 66 Air Chart, one must delve into the parallel histories of American ground and air transportation. In the early days of flight, long before the era of modern radio navigation, pilots relied on what was essentially a visual flight chart of the country below. A primary form of this was following prominent ground features like railroad tracks and major roads.

The establishment of a rudimentary air navigation system began in the mid-1920s with the U.S. Lighthouse Service. For nighttime flights, they erected beacon towers spaced every 10 to 15 miles. For daytime navigation, they constructed large, yellow-painted concrete arrows at the base of each tower, directing pilots to the next beacon.

By 1929, an air corridor was developed that became a central part of the Midcontinental coast-to-coast airway, following the Santa Fe Railroad tracks from New Mexico into Arizona. This route was a significant milestone in early passenger service and was developed by the Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT) company, with the legendary aviator Charles Lindbergh leading its technical advisory team.

The user may initially assume that the aerial route was created to specifically follow the highway. However, a closer look at the data reveals a more profound relationship. The TAT airway’s alignment with the Santa Fe Railroad and the subsequent construction of Route 66 along a similar path were not a direct cause-and-effect relationship. Instead, all three transportation corridors—the railroad, the highway, and the air route—followed the most logical and geographically feasible path through the rugged terrain of the American West. The air and ground routes were not designed for each other but co-evolved along the same fundamental corridor, a testament to the common-sense principles of travel. This is a subtle yet crucial point that moves the analysis beyond a simple parallel to a co-evolutionary narrative. Today, the “Route 66 Air Tour,” as a real-world example, is a symbolic act of reconnecting these parallel histories, with pilots flying over the historic highway and visiting museums and sites that preserve this shared legacy.

The end of the visual airway system came swiftly with technological advancement. The advent of new radio navigation aids and airline mergers rendered the ground-based beacons and arrows obsolete. The system was decommissioned, leaving the concrete markers as silent historical relics on lonely hilltops and mesas across the landscape. For an aerial explorer, these surviving markers are tangible waypoints to the past. Specific examples include the Cuervo CAA Intermediate Airfield, with its visible runway circle, and the 9-Mile-Hill Beacon west of Albuquerque. The Cibola County Airway Museum at the Grants-Milan Airport even features a restored beacon tower and generator shack.